By Thomas Meyers

Originally published in Massage & Bodywork magazine, August/September 2004.

Continuing last issue’s Structural Integration (SI) theme, let’s explore a tangent that has implications for everyone in the bodywork field. If there’s one thing that characterizes the approach to integrative bodywork, it is depth. Most of us were drawn into bodywork because we found a deeper experience of our own bodily self. And we choose to do this work to give that depth of experience to others. But how do you get deep? How do you convey the experience of depth? What does “deep” really mean in the context of the body?

Depth has been a challenge for SI since its inception. Part of the reason it got such a reputation for pain is that Ida Rolf kept exhorting her students to “Go deeper!” Those of us who started out in this craft in the 1960s and 1970s, in the first rush of pioneering enthusiasm, took “go deeper” to mean “go harder.” We had calloused knuckles and low tables for really leaning into the clients. It was definitely a limitation in our understanding and perhaps a limitation in her way of teaching. More than two decades later, even though the teaching of depth in SI schools has changed considerably, the reputation of what Rolf’s work is like lingers on.

A Singular Moment

My own journey into depth was changed by Rolf herself in a singular moment. In 1978, I was in the midst of my advanced training with her. As it turned out, this was Rolf’s last training — she was to die of congestive heart failure and complications from rectal cancer less than six months later at the age of 83. During this training, she spent most of her time in a wheelchair, although she could still walk for short distances. Mostly, she directed the work of others, though she occasionally would do some hands-on work herself. Her eye was still baleful, and her voice still strong, and my armpits were ringed with the honest sweat of the anxious any time I worked in her presence. (See Figure 1)

On this particular afternoon, I was working with Tweed, my bodywork model. Tweed was a nurse, a bright and gentle soul, who unfortunately was compelled to live with a severe idiopathic scoliosis, which had strongly distorted her rib cage and spine. At that time, I was living and working in Little Rock, Ark., and Tweed, who had benefited greatly from our first 10-session series (I had learned a lot, too), had traveled all the way to Philadelphia to be my model for advanced sessions under Rolf’s direction. This afternoon, Rolf’s eyes had passed from baleful to increasingly frustrated. Tweed was seated on a bench, slowly bending forward over her knees, while I stood behind her, using the flat of my knuckles to open the locked myofascia in her knotted erectors.

Rolf was fidgeting in her wheelchair, saying, “Get in there, man!” or the familiar “Go deeper” — at which I would redouble my efforts, and Tweed would grin and bear it as her back got redder — but not longer. Finally, Rolf could take it no more. She wheeled her chair over closer to the back of the bench, barking my shins with the footrests. She jammed on the wheelchair brakes so the chair wouldn’t move, and then leaned way forward. At full reach from the chair she was just able to put two gnarled fingertips on either side of Tweed’s sinuous trail of spinous processes. Slowly her fingertips traveled down Tweed’s twisted spine.

Tweed was bent way forward with her head down and so did not know Rolf and I had changed places. “That’s it, now you’re getting it!” she cried, as her back started to let go of another layer of long-held tension. At this moment, I realized that depth was going to be an elusive and hard-won property. If this failing little old lady could achieve more depth with two fingertips at full reach out of a wheelchair than I could in my young prime standing right over the client with my fists firmly placed in her back, then certainly going deeper and going harder were not even remotely equated.

The Language of Depth

Of course, a truer language of depth than “Go harder to get deeper” has suffused our profession in the years since. For me, increased exposure to cranial, visceral, and inner sensing work has changed my whole perception — sometimes it is the softest or lightest touch that reaches most deeply into the body. Certainly the heavy-handed practitioner is doomed to stay at the surface, held there by the client’s (intelligent) resistance.

And body-centered psychotherapy asks another question: Is deeper in the body the same as deeper into the person? By reaching into the realm of somato-emotional release, methods like Hakomi, the Rosen Method, Holotropic Breathwork, and Dr. Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing can reach into the depth of the nervous, hormonal, and organ systems with no literal touch at all.

And homeopathic results show that the lightest touch of chemistry can often have a much deeper healing effect than the heavy hand of medical prescriptions.

But if we stick to the hands-on modalities practiced by many of the readers of this magazine, the conundrum remains: How do we get genuine depth without creating the kind of sensation from which clients withdraw? The two obvious choices — work superficially and hope for the best, or bruise your way on in and “force them changes” — are simply not acceptable. But, of course, they are not the only choices. (See Figure 2)

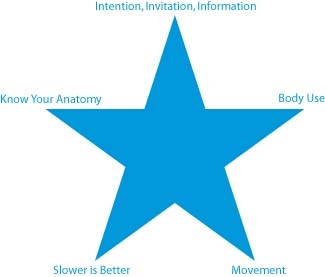

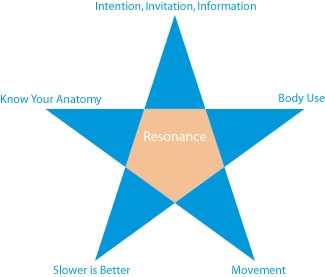

Now that I teach more than I practice, conveying the slippery skill of depth without pain occupies many of my waking hours. Here is a summary list of my current thinking on the five points of depth, with a brief explanation following each:

1) The Three Ins: Intention, Invitation, Information

A clear intention precedes your fingers into the tissues, so the mind and body are aligned. Do you know what your intention is each time you enter the field of the other person? Having a clear intent makes achieving depth so much easier for both of you. If your intention

is muddy, or you are just going in to look around, the client’s tissue is unlikely to open up in front of you to allow you in.

Each move is also an invitation — I love this word, it means “bringing life in” — an invitation to greater awareness, greater movement, greater relaxation. If your hands are suffused with the attitude of invitation as you come into the body, the waves of tension and resistance part in front of you, and depth is more easily found. Entering and waiting, or bringing tissue toward you instead of pushing it, can be a literal expression of this inner “invitation.”

And finally, each move informs — brings in form. That is the uniqueness of bodywork, Deane Juhan tells us: Nothing is added but information, nothing is subtracted but patterns the body releases. Hands-on work is essentially an educative process. If we come into the body with the intention of inviting the tissues to take up information they might be missing, our work is very different from when we come in with the intention of fixing it — breaking up that fascial adhesion, stretching that spasmodic muscle, annihilating that trigger point, whatever.

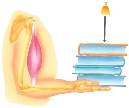

2) Practitioner Body Use

Effective body use on the practitioner’s part is a second essential element — using your muscles to force a change in tissue is a great way to guarantee that the disturbance to the client will be much greater than if you use your bones and your weight. Not only will you generate resistance in your client if you muscle your way in, but your hands and shoulders will likely not serve you well for a long career. Fall into the tissue, and let it melt. The absolute minimum force to get the job done while maintaining maximum sensitivity to the many levels of the client’s state, both local and global, is our goal here. Good practitioner body use, seen in this light, becomes more than a good idea, it’s the law.

The law in question is the Weber-Fechner Law, which states that any muscle is sensitive to changes in load greater than or equal to one-fortieth of the load on the muscle. If you come into the body with three pounds of pressure, you will feel changes of about an ounce or so. Come in with 40 pounds of pressure and your client will have to make change that amounts to a pound or more for you to feel it.

In other words, the more muscle tension I have as I work, the less sensitive I am going to be about the changes going on in the client’s body. Conversely, the more lazy and relaxed I can be, the more exquisitely I will enter the client’s kinesthetic world, feeling the myriad rhythms in the tissues of her body. Working with (as opposed to “on”) those rhythms is in itself healing. Your body use is the largest single component in being able to sense your client’s inner, below-the-conscious level experience. (See Figures 3A and 3B)

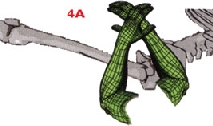

3) Client Movement

Rolf described her method in one sentence: “Put the tissue where it belongs, and call for movement.” Too many of us forget the latter part of the sentence — especially when some massage trainings can leave us with the impression that the client is a passive recipient rather than an active participant. You want the client to relax, so why should we bother her with movement? Having your client lie passively is great for spa or relaxation massage, but if your goal is remedial or integrative, and if you want to help her experience the depth of her body feeling, then client movement during the session is essential.

Of course such movement is good for the client — it keeps her engaged, activates the body image, helps reset the muscular “tone-o-stat” — all part of dispelling sensori-motor amnesia. Less recognized is how important client movement is for the practitioner. When the client is moving, you can feel exactly what layer, what depth, your work is reaching. (See Figures 4A and 4B)

Try something you usually do on one side of the body while your client lies still and then on the other side with your client moving. It doesn’t have to be a huge movement — a few inches is plenty, oblique to your direction through the tissue. If you listen to what’s under your hands, you will find that it is much easier to know where you are, yes? The practitioner’s secret benefit to client movement: If you are lost, get your client to make small moves under your touch; it will be better for them, and it is as if someone turned the anatomical lights on for you. Keep them moving when you are working.

4) Slower is Better

Speed is the enemy of depth — the faster your hands go, the more resistance you generate. Waiting and sinking and swimming slowly through the tissue takes a little longer — but like the tortoise, wins the race. How fast is determined by two simple questions. First, is the tissue melting in front of your fingers? If you have to pry it open, you are going too fast. If nothing is happening and you are bored, you are probably going too slow. If it is melting just in front of your hand (or elbow or whatever), you are sitting in Goldilock’s seat — just right. The second question is in your perception of the client: Is she trying to get away from what you are doing? If your work includes the client having what Rolf called “the motor intention to withdraw” — she is pulling away, even a little — then, in my opinion, you are going too fast. (See Figure 5)

I make occasional exceptions to this rule when confronted with physically traumatized areas where there is so much pain stored in the myofascial tissues that I will cross the line into directly painful touch — but this is with the conscious consent of the client and only after rapport is established — which I usually maintain with eye contact during the painful work. The intent must be to “expose” any stored pain, not “impose” more pain.

5) Know Your Anatomy

I’ll admit my prejudice — teaching anatomy — but I find that depth is also a function of ever-more-precise pictures of exactly what is under your hands. If I can reconstruct the picture of where I am in my mind’s eye and connect that image to what I am feeling in my hands, my intuition and my ability to go deep improve by leaps and bounds. If I am lost in a wash of tissues whose orientation and purpose I am not clear about, my intuitions become vague and fairly useless. (See Figure 6)

Learn your anatomy — don’t abandon the effort because it is an endless barrel of detail, full of latinate words. The new anatomy books and other products that are now out give you many alternatives to just boring away at the boring books. Filling in the pictures with your felt sense does more than anything else to allow you into the depths of the body’s tissues, unlocking the secrets of ligaments, tendons, and best of all, the anomalies that make each of us individual and unlike the book.

Resonance

If the five points of depth are the five points of the star, in the center is the concept and experience of resonance. There are so many rhythms in the body — the rise and fall of breathing, the beat of the heart, the hum of metabolism, the buzz of the brain waves, the idling purr of muscle tonus, the ebb and flow of the cranial pulse, the deeper wash of the long tide, the irregular grumble of peristalsis, the reciprocal metronome of walking, and perhaps a hundred more drumbeats, known and yet-to-be known. Training your awareness to your favorite pulses and increasing your sensitivity to the biologic rhythms allows you to enter a state of resonance with your clients. When you are so linked, your ability to make deep change, to obtain access to the deeper layers of tissue, as well as the deeper layers of being, increases wonderfully. Spend even one day breathing in tandem with your clients, and then assess that day’s results. (See Figure 7)

What would you add? What is your experience of depth, and how do you attain it? Depth is an elusive concept, an artistic experience, a mysterious property. In my opinion, these five points are the doors that lead to real depth work, but the final step is always for you and the client to walk through the door.