By Debra Curties, R.M.T.

Originally published in Massage & Bodywork magazine, June/July 2001.

Breasts are body tissues with their own health needs. At some point in time, most women will experience breast congestion, breast pain, discomforts of diagnostic or surgical procedures, and anxieties about lumps or other changes in their breast tissues. Pregnancy and breastfeeding have their set of associated breast tissue needs. Unfortunately, many women experience physical and psychological trauma related to their breasts. And then there is breast cancer — impacting directly on the lives of many women, and indirectly on all of us.

Conditions and occurrences affecting breasts lead women to seek medical help and to self-medicate. Statistics indicate many women complain of breast pain to their doctors. At the same time, most sources reporting these stats believe women underreport breast problems, presumably for similar reasons to those which lead us to be uncomfortable about breast massage.

The fact that breasts are strongly associated with sexual touching and attractiveness does not mean they cannot or should not receive health care. In fact, this symbolism adds a set of psychoemotional concerns many women need help with in order to feel more at ease about doing routine self-examination and seeking the therapies they need in a matter-of-fact way.

The multidimensional significance of breasts means health care practitioners involved with breast health must be carefully trained. We need to be able to deal with the significance and sensitivity involved in touching breasts, we need to be able to communicate clearly, and we need to know how to maintain good professional boundaries.

I cannot ascribe to the thinking that by examining or treating a breast (with consent), a trained health care practitioner is by definition doing something sexual. A therapist with sexual or abusive intent can convey this in the way he or she touches any body part, and with all manner of other verbal and non-verbal cues. The well-intentioned therapist will be especially conscious of avoiding any such possible interpretations when treating body parts known to be more emotionally charged. We assume doctors, nurses, lab technicians and others can appropriately handle the necessities of working with breast tissues. Are massage therapists so different?

Massage therapy is an effective “wellness” treatment for breasts, as breasts particularly need good circulation and tissue mobilization for optimum health. Poor circulation can produce various uncomfortable symptoms. Breast scarring (surgically and traumatically induced), which is more common than we often realize, can cause painful syndromes and obstruct blood and lymph flow. Some believe there may be a correlation between chronic poor breast drainage and susceptibility to malignancy. Massage techniques and hydrotherapy may in fact turn out to be some of the most effective modalities for addressing such problems and promoting breast health.

Many women need more help becoming comfortable with breast self-examination than they receive in their doctors’ offices. Some have traumatic histories and need assistance achieving a sense of normalcy about their breasts and the types of touch involved in seeing to their care. As well, a skilled palpator may be more successful in picking up early-stage breast tissue changes needing medical follow-up than a client would herself. Given the time spent, the regular treatment intervals, the privacy of the circumstances, and the trained empathy and physical skill of the practitioner, massage therapists really have something to offer.

There are some very important safety concerns, both for the client and the practitioner. Some people have histories which can make it difficult for them to distinguish present realities from past experiences, and some people find it especially tough to talk clearly about what they accept and cannot accept as treatment — referring to both clients and health care workers. Our personal stories are often the same. There are no magic answers about how to identify the situations to avoid. Most of the confirmed disciplinary cases I am aware of have arisen from circumstances where the massage therapist did not communicate clearly, did not properly obtain consent, and/or did not maintain professional boundaries. However, there are some definite risks — there are high-risk clients and there are high-risk circumstances. It is important to keep in mind these circumstances are not exclusive to breast massage. Getting a good, basic education, finding a peer support group or a skilled supervisor once out in the field, and pursuing advanced training in specialized areas of treatment and client interaction are important safeguards.

Can we justify letting our concerns about risks cause us to completely overlook the legitimate treatment needs of breasts? Is it right that breast health care is not getting the attention from our profession that it should? Should women have to suffer from pain and other symptoms that could be ameliorated if we were comfortable addressing them in the way we would be for other body tissues? Is there any way massage therapists can help in the fight against breast cancer? These are important questions, and it is our duty as members of the professional health care community to give them serious thought. Breast massage will not be right for every client and every therapist, but are we doing our best to fulfill our profession’s obligations? Are we wrestling in a principled way with the dilemmas involved or are we putting our heads in the sand?

Personal Experience

One of the things we often forget when we become focused on the discomforting issues breast massage raises, is that it can have real and important benefits for our clients. While I’ve heard hundreds of stories from women, I offer you my own, because it is often experiences I have as a client that nurture my faith in the efficacy and value of massage and remotivate me as an educator. A few years ago I had a painful, deep biopsy in one of my breasts. It happened rapidly after one of those scary “found a lump” scenarios. Almost before I had time to think, I was in the OR. Fortunately, it was found to be an irregularly shaped cyst and I knew in my head I was all right. The incision had gone straight down through my breast, which was bruised, hard and swollen, and had a fair bit of nerve irritation. Two weeks later there wasn’t much relief and I still hadn’t thought about getting breast massage (you tell me why?). In the third week I booked an appointment, asking for breast massage and neck work, since my neck was also sore from the intubation. Within the first five minutes of treatment, I felt the sense of frozen apprehension begin to leave me; as the treatment progressed, I could feel my neck, shoulders and jaw let go of a terrified holding I wasn’t really conscious was still stuck in my body. The first breast massage was simple and soothing; after this first session my symptoms improved by approximately 50%. Four breast treatments in three weeks were enough to restore normal softness and circulation to the breast tissues and healing proceeded quickly and uneventfully.

Anatomy and Function of the Breast

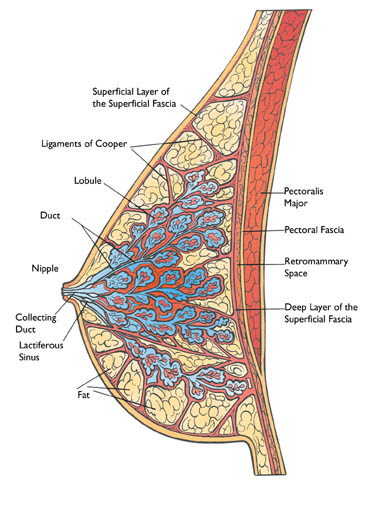

The breast is a specialized gland structure that evolves essentially as an appendage of the skin. It develops within the layers of the subcutaneous superficial fascia. The most superficial of these fascial layers is positioned directly under the skin and forms the anterior boundary of the mammary gland. The deepest layer forms the posterior boundary and sits over the muscles of the chest wall. The tissues which make up the breast lie in between, anchored by extensions of these fascial membranes, and known as ligaments of Cooper or Cooper’s Ligaments. These thickened fascial strands extend into the breast to provide a supporting framework. Cooper’s Ligaments are also called the suspensory ligaments. They are illustrated in Figure 1.

Deep to the point where the breast attaches to the posterior layer of the superficial fascia is a zone of loose areolar tissue called the retromammary space. The arrangement of loose connective tissue in this space allows the breast to move fairly freely over the fascia covering pectoralis major. The retromammary space also plays an important role in the lymphatic drainage of the breast, as we will discuss shortly.

The rounded contour of the breast projects anteriorly from the chest wall and suspends loosely against gravity. There are no muscles or cartilaginous structures within the breast, so it relies on its fascial envelope and suspensory ligaments for integrity and support. This information is important for the massage therapist, who should avoid techniques that could unduly stress or stretch these structures.

In the center of the breast’s surface is a circle of darker skin called the areola. While usually a somewhat deeper version of the woman’s skin color, the areola can become very dark in high estrogen states like pregnancy. The skin of the areola contains a large number of specialized sebaceous glands, referred to as Montgomery’s glands, which are clearly visible as small bumps.

The nipple is positioned at the centre of the areola. Both the subareolar tissue and the nipple are richly supplied with smooth muscle that runs in both circular and radiating patterns. When these muscle fibers contract the nipple erects, and if the woman is lactating, the milk sinuses empty. The nipple is also a centre of sexual sensation and is served by a large number of sensory nerve endings.

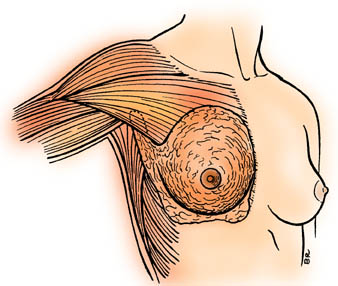

Look closely at to compare the protuberant breast contours (left breast) with the boundaries of mammary tissue as shown on the right side. This information about the actual extent of breast tissue is very important to the practitioner because findings of breast tissue tenderness, nodularity, and benign and malignant lumps may all occur in this larger zone beyond the contours of the breast. These thin, extended layers may also swell painfully with inflamed or engorged breasts.

The breast overlies several muscles. On average, 50% of the breast sits over pectoralis major, and the rest over the other muscles of the chest wall, especially serratus anterior. Variable small amounts of breast tissue overlie latissimus dorsi superolaterally, and the lower edge covers a bit of rectus abdominis.

It is common and quite normal for a woman’s two breasts to be different sizes. The most common breast abnormality is presence of one or more accessory nipples, usually found along the “nipple line” in the abdomen. Another frequently occurring breast irregularity is a greater than average extension of breast tissue into the axilla. It is important to be aware of this anomaly, because it can look like a mass. The tissue will not appear ominous in that it is malleable, its boundaries are soft and easily palpated, and it moves well in relation to nearby tissue. Doctor examination is necessary, however, to ensure the formation is simply extra breast tissue.

Specific Breast Massage Guidelines

As has already been said, the standard general rules and guidelines governing massage therapy apply to breast massage, but perhaps more stringently. This statement is particularly true with respect to therapeutic relationship requirements about communication and consent.

What follows is a summarized list of guidelines applied specifically to breast treatment:

1. Communication, Trust, Consent

• The client responds best to openness, trustworthiness and common sense in the practitioner. These qualities allow her to form an opinion about the therapeutic relationship environment in which she would be consenting to receive breast massage.

• Most clients need time to consider breast massage. This can include having informational materials to take home, knowing about her options within the treatment protocol and taking time to think about her reactions and requirements, being given names of clients willing to receive calls from someone considering having breast massage, and having access to as much dialogue with her massage therapist as she needs to feel comfortable.

• The male massage therapist should always offer to refer the client to a female practitioner for breast massage and should have available a list of suitable referrals.

• Breast massage should not proceed until good communication and client-therapist trust is established, and the parties have been able to achieve a mutual level of comfort with respect to the proposed treatment plan.

• The consent dialogue must include discussion of the possibility breast massage may induce emotional reactions or invoke painful memories. The client needs to consider how comfortable she is with this possibility and whether she has an adequate support system in place should she need assistance to deal with reactions like this.

• Breast massage cannot automatically be included in other massage therapy protocols. It is a type of treatment that must be consented to separately and specifically.

• Consent for breast massage must be renewed before each session. The client must clearly understand she has the right at any time to state a preference, alter or discontinue the treatment plan, or choose not to have breast treatment on a given day.

2. Guidelines for the Therapist

• The massage therapist has the right to decide not to offer breast massage to a particular client, type of client, or at all.

• The massage therapist who cannot achieve good boundaries or professional neutrality must self-disqualify from providing breast massage, in general, or in the case of any client who evokes such concerns.

• The practitioner’s choice not to offer breast massage must always be communicated in a manner that does not shame or judge the client for seeking out breast treatment.

• Regardless of the specific indications in a client’s case, breast massage should always be given in the spirit of aspiring to enhance a woman’s positive relationship to her breasts and commitment to breast health care.

• The conscientious massage therapist assumes responsibility for helping a client familiarize herself with her breast tissues, for supporting regular breast medical evaluation and self-examination, and for encouraging breast self-massage.

• The massage therapist must not sexualize the breast massage situation. This includes refraining from using language about breasts or making statements about a client’s breasts which create a sexual inference. The therapist must avoid touching or in other ways stimulating the nipples. Any indication from a client that she finds the breast treatment arousing does not change the practitioner’s responsibilities in these respects.

• The practitioner must make every attempt to self-monitor for personal issues and reactions which might jeopardize the integrity of the therapeutic relationship. He or she must also seek to be present and focused during breast treatment to avoid creating an atmosphere which could be misinterpreted. Overly-sensitive or solicitous behavior is also to be avoided.

• The practitioner must seek out training adequate to the demands of his or her practice. In the breast massage context this could include both technical skills training and therapeutic relationship skill-building. It may also include advanced education in handling more complex psychoemotional situations.

3. Technical Guidelines

• Breast massage techniques should be designed to enhance and support lymphatic drainage, the predominant drainage system of the breast, incorporating the understanding that most lymph flow in the breast is anterior to posterior.

• Breast treatment will be most effective when it is preceded by relaxation of surrounding musculature which can compress on its neural and circulatory supplies, in particular pectoralis major.

• Manual techniques should not overstress or overstretch the supporting membrane structure of the breast.

• Draping procedures will always conform to the client’s wishes.

• It is especially important the client feels warm, comfortable and physically secure for breast work.

• The massage therapist needs to keep in mind that painful breasts, recent surgery or trauma, some breast conditions, and the presence of breast implants may necessitate positioning adaptations during general massage therapy. Prone position, and at times sidelying, may be too uncomfortable to be utilized.

4. Special Considerations

• Standard, post-surgical guidelines apply when treating a client who has recently had a breast procedure. These include observation for complications like thrombosis, particular attention to hygiene in the vicinity of the incision, caution about compressing or displacing drainage tubes, caution during positioning and turning of the client, application of hydrotherapy which is consistent with tissue tolerances and the efficacy of local circulatory channels, and avoidance of overly-early stressing of the incision site and repairing tissues by manual techniques or passive movements.

• If the client has or has had breast cancer, the massage therapist needs to be familiar with risks, adaptations and guidelines pertaining to massage therapy for the person with cancer. This important subject involves a number of aspects which require the massage practitioner’s attention. Breast cancer does not have specific or unique features in this respect; however, it is important for the practitioner to be knowledgeable about and feel comfortable with the blend of breast massage and cancer-related considerations.

• For clients with mastectomies, breasts which have been removed, like other “phantom” parts, often have an energetic presence for the woman. The tissue area should be approached with the sensitivity and respect accorded to breasts.

• Massage therapists should have an awareness of stability and obsolescence concerns related to breast implants.